20-year-old Arthur Williams married Lucy Gibbons on Saturday 16th December, 1939. Their marriage licence cost £1 and 10 shillings. Arthur was a plant maintenance fitter at Pazo works in Oldbury and prior to that he worked at K & J’s. He just had received his call up papers up in October. Ironically, if he had stayed at his old job at K & J’s he would have been in a ‘reserved occupation’ and thus ineligible for conscription. However, he was now in training as a sapper with the Royal Engineers at Colchester.

Arthur and his fellow soldiers landed in France in April 1940. He wrote home to his family telling them: ‘It’s a pretty decent place here but there are no amusements.’ On 10th May, the Germans invaded Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg and the BEF engaged in battle with them. Before long his company were falling back to Dunkirk, blowing bridges along the way, the enemy hot on their heels. They stopped for water at one village only to find that the French police had chained up the local well and did not want them to have any water for fear of German reprisals. The engineers promptly blew off all the locks, along with the roof.

On the first day of the evacuation at Dunkirk, only 7,669 men were withdrawn, but by the end of the eighth day a total of 338,226 soldiers had rescued by a hastily assembled fleet of over 800 boats, many of which are pleasure craft, fishing boats, small merchant marine boats and lifeboats. While some troops were able to embark from the harbour, a great majority, including Arthur, had to wade out from the beaches, waiting for hours in the shoulder-deep water, while being shelled and strafed.

Image above: Water damaged photograph of Lucy carried by Arthur. Postcard sent from France on 5th May, 1940, five days before the German Blitzkreig. On the back he wrote: ‘My Darling Wife, I’m alright and well. Hope you are OK. I hope you like the card I got this afternoon in the town. Love Arthur xxxxxxxx’. Photograph of Arthur (on left) Colchester, 1940.

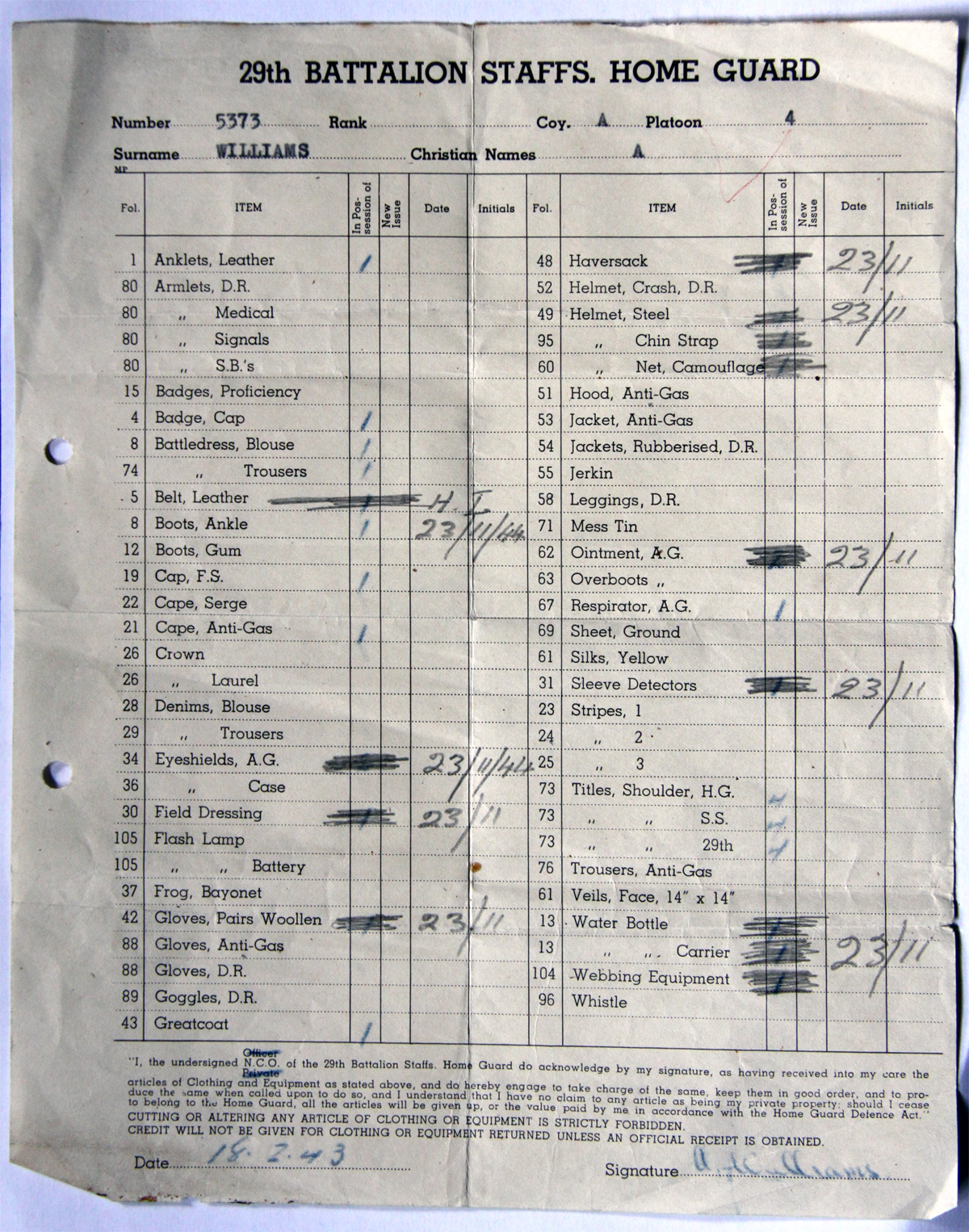

At this time, his wife Lucy told her family she dreamt that he was in water of some kind. She fainted as he walked through the door on his return. He arrived home without his boots, in a singlet, with just a ten bob note and one precious photograph of her that he had kept all the time while in France. He thanked the Salvation Army for meeting them on the dock in England with ‘tea and a wad’ but was otherwise tight-lipped about his experiences over there. He was transferred to the Territorial Army Reserve and because of his engineering skills was placed in a reserved occupation at K & J. He did not return to France and rarely talked about his experience. He went on to serve with the 29th Battalion of the Home Guard at Carters Green, with the rank of sergeant.

– from the book ‘West Bromwich at War, 1939-45’