Loraine Craig (Nee Hooper)

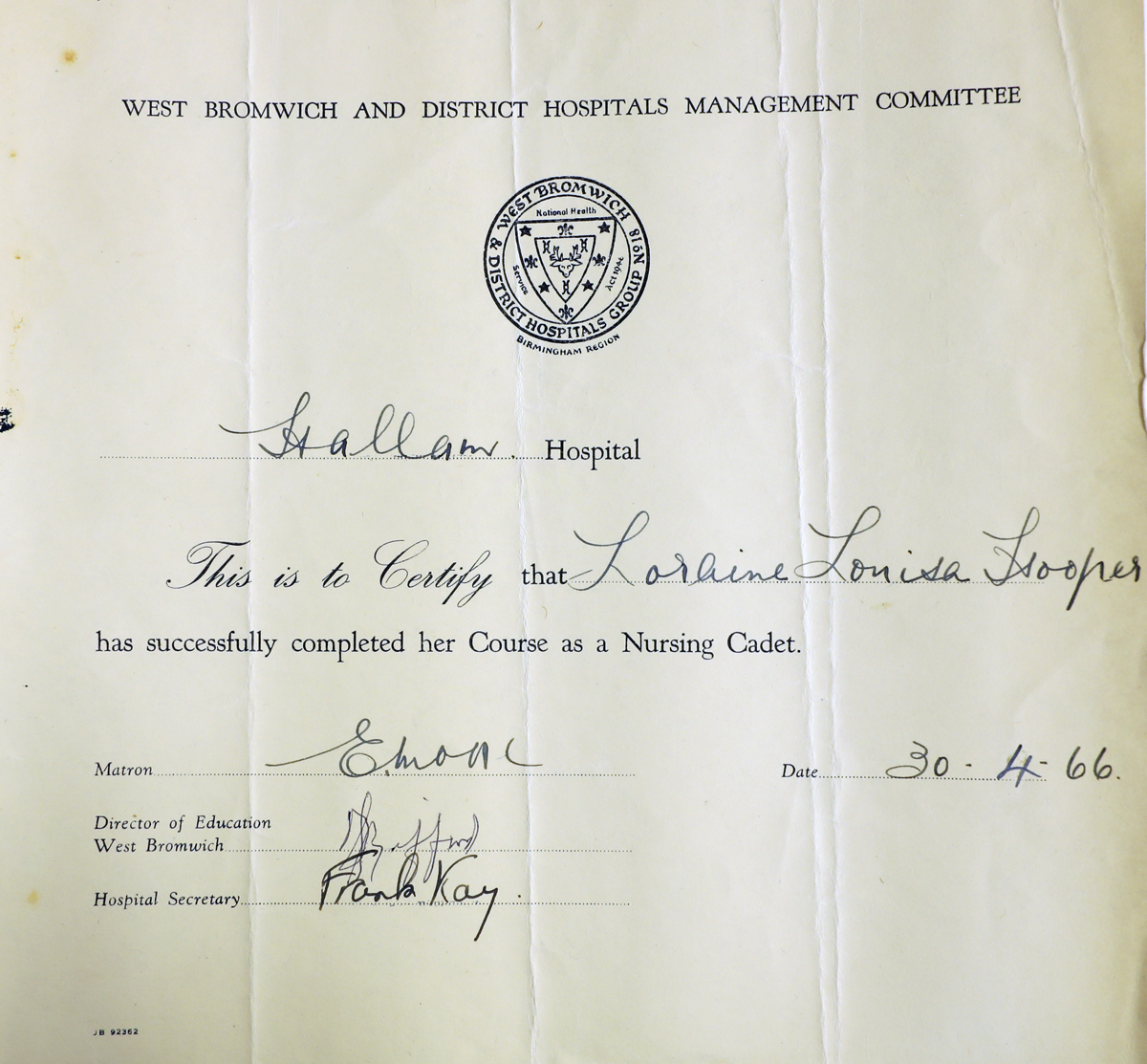

“I began my nursing training at Hallam Hospital, West Bromwich, in September 1964, as a cadet. There was an entrance test, which consisted of a book with different patterns on each page – each pattern had a section missing. At the bottom of the page were several patterns; you had to choose which pattern went into the missing square. After completing the book, you had to write a short essay on a choice of topics; mine was leisure time. You required two GCE’s (General Certificate of Education) to enter state registered nursing; these being firstly, English Language and secondly, Anatomy and Physiology. These you gained by attending the West Bromwich College, which was then situated on the High Street one day a week. Your exams for these qualifications were undertaken at the college after 12 months.

The preliminary training school was in Beeches Road. The main tutors were Miss Tucker and Mr Plant, but later in my training it was Mr David Cooper, Miss West and Mrs Avis. I was a cadet nurse until May 1966, your cadet uniform, was a yellow dress, brown shoes, lace-up and polished. I worked in the X-ray department for 12 weeks, which involved fetching patients from the wards to have their x-rays taken, then returning them to the wards, dealing with outpatients attending the X-ray department, and general cleaning of the X-ray rooms, stocking items such as gowns, sheets, stationary.

After the X-ray department I worked in the Pharmacy Department; my work there entailed washing medicine bottles and sterilizing them in a small autoclave, then replacing them in size order back onto the shelf, general cleaning and restocking stationary items. After Pharmacy, I worked in the Nursing Home with the Home Sister, Miss Crow, a very strict lady. My work there was to book clean linen into the nurses’ rooms on a strict rota, clean bathrooms and toilets, clean rugs, put laundry away neatly on the correct shelves, with folds showing as neat lines, collecting dirty laundry. At that time the laundry was at Hallam Hospital. After the Nursing Home, I worked in the Sewing Room, with a lovely lady called Mrs Powell. I would go to the wards to help Mrs Powell change the curtains around the beds. I would sort out the linen, sheets, pillowcases, and towels that required repairing. There were two other ladies who had needle sewing machines to do the darning. Nurses would come to the sewing room to have new uniforms measured and altered. Doctors would come to have their white coats and theatre uniforms. All uniforms for domestics and physiotherapists would be collected from the sewing room. On a Thursday afternoon I would have to help out on Ward 6, which was then a ward for Electroconvulsive Therapy, which was then a treatment for depression. I would look after the patients as they were coming around from their sedation and would make them a cup of tea.

Our working week was Monday to Friday, 9-5. Tuesdays we were at college and on Saturday we worked 9-12 in the departments, but after 12 midday we went to Ward 5, which was a mixed geriatric wards to help feed the elderly who were unable to feed themselves.I thoroughly enjoyed my cadet training and learnt a lot, interaction with the public, learning new skills, mixing with other nurses and being in awe of how much they knew.

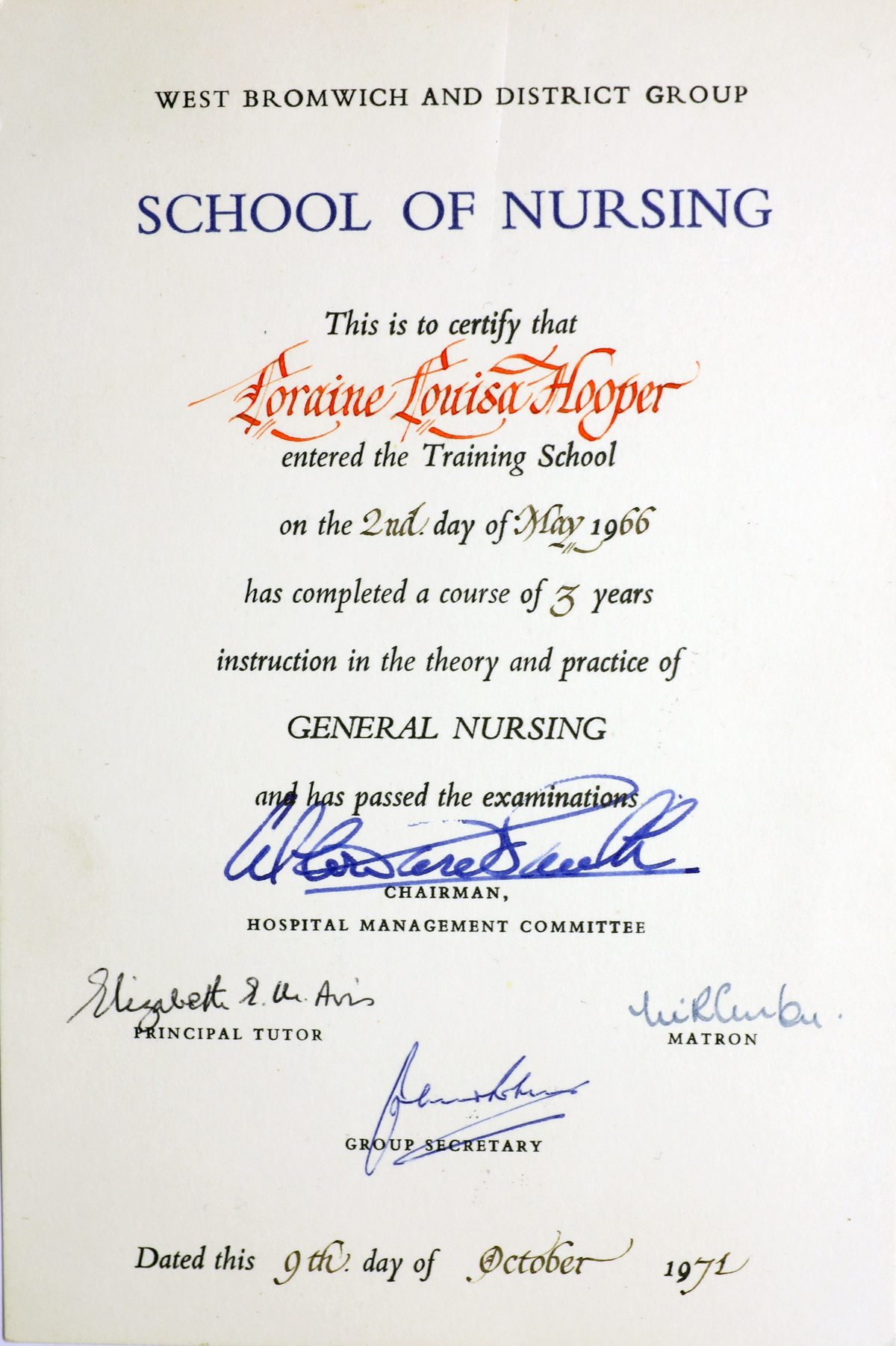

I entered nurse training in May 1966. Our tutor was Mr David Cooper – his favourite sayings were ‘Dead as a Dodo’ and ‘Forever an a fortnight’. We sat in a classroom in rows at desks similar to our junior schools, we were taught the rudimentary basics of nursing: bed-bathing a patient, washing a patient’s hair while they were in bed, making beds, hospital rules, cathererisation of females, skin-care and nails, pressure areas, how to give subcutaneous and muscular injections, a septic technique in changing a dressing, taking sutures out of a wound. There were no sterilised dressing packs then, the instruments had to be boiled in a sterilizer. The gauze dressings were taken from a drum and placed into two kidney dishes (sterilised) one on top of the other.

We had written tests at the end of three months to assess our knowledge. We were allowed to go on a ward for half a day under supervision to learn on the ward; this involved us walking from Beeches Road to Hallam Hospital in our uniforms under a plain navy blue mackintosh gabardine coat. Our uniform was a pale blue short-sleeved dress, a white starched apron, clean every day, a white plain starched cap, and black laced up shoes, polished, American tan stockings/tights. Hair wasn’t allowed to be on the collar, no jewellery, and no make-up. As we progressed through our three-year training, we had blue stripes added to our collars to indicate which year we were in. Every year we had to do three months on night duty, when we were in training school for study days we worked a rota of three nights on duty and four nights off duty, but if we weren’t on study nights the rota was four nights on duty and three nights off duty.

We had lectures at Hallam Hospital from the consultants in their own sphere of expertise. At the end of each year we sat an exam, which on passing we went to our next year with more respect and responsibility. We could speak to the Sister ourselves then, instead of going through their chain of senior nurses.If there were any thermometers broken, a nurse (usually the junior one) was nominated each week to take the broken pieces to Matron on a Monday morning on a silver tray, each broken thermometer was 5 pence (in old money) deducted from your salary whether you had broken it or not.

You had to report to Matron when you were going on holiday and on your return, if you had been away ill, you had to do the same thing and you may be put back three months in your training if you had too much absence due to illness. We worked a 42-hour week and our monthly wage was £40. Our duty shift was over five days, which could be:

7.30 am – 9 am (then off duty until 1pm, then on duty until 8pm)

7.30 am – 1 pm (then off duty until 4pm, then on duty until 8pm)

7.30 am – 6 pm (there were two of these shifts each week).

7.30 am – 3.45 pm (which was your half day)

Weekends off were rarely given. Night duty shifts were 8pm – 8am.

After our three years of training we sat our hospital finals, which we had to pass first before we could take our state finals.

At Hallam Hospital there used to be a small training room which was used for lectures and taking examinations. The examination consisted of a written multi-choice questions and an essay. I think for the oral examination there were eight examiners covering a different aspect of nursing – orthopaedic surgery, urology, gynaecology and theatre. There would be a patient in bed in the room and questions would be asked about him/her. My patient was a young man I had been to school with and when he saw me he smiled and said, ‘Hello Loraine, fancy meeting you here’, to which I blushed deeply, and the examiner glared at me and tutted very loudly. I was really glad when my 15 minutes were up around his bed.

Our state finals had to be taken at Bromsgrove Hospital as there was building work being done at Hallam, so it was too noisy. The sister on the ward I was working on gave me a late shift of 7.30am to 1pm and back on duty at 4pm until 8pm. I requested could I leave at 12 midday, as we had to catch two buses to get to the hospital, one to Birmingham and then one to Bromsgrove. This request was granted. All our group set off, asking each other questions and getting different answers form everyone. It was very noisy on the top deck of the buss. We duly arrived at the hospital in Bromsgrove, went to the examination room – again eight examiners, a patient and a bed. I can recall some of the questions were about varicose veins, gynaecological instruments and bed bathing an elderly gentleman who had a stroke. Nerve wracking.

We all finished about 5pm. Travelling back on the buses we discussed what questions we had been asked and the answers we had given. We were much more subdued coming back. I went back on the ward at 7.25pm, I did two blood pressure readings, then sister allowed me to go home.

The results of the exam came out six weeks after and at this time I was working on a mixed E.N.T ward, male, female, and children. The ward was situated on the mezzanine level with a balcony, lovely to sit out on summer days. I asked my Mom not to tell me the results of the exam when the post arrived in case I had failed as I would be upset and crying, and if I had passed I would still be upset and crying. In those days the switchboard operators would sit in the telephone exchange at the rear of the Porter’s Lodge at Hallam. The telephone on the ward rang about 11am and I answered it, saying ‘Ward C3, Nurse Hooper’. The caller asked to speak to Staff Nurse Hooper to which I replied we had not got a Staff Nurse Hooper on the ward, to which the switchboard operator Doreen said, ‘Idiot, I am talking to you. Congratulations.’ I was ecstatic, but I went home and didn’t say I knew to my parents, who were delighted to tell me and they bought me a fob watch with my name engraved on it.

I stayed on C3 for 18 months following my registration I left after getting married in 1970, but returned to the District Hospital in 1975 to work as a Bank nurse on Bache Ward.

The Staff Nurse uniform was: Sky blue dress, white apron, linen starched cap, cuffs, Petersham belt with silver buckle, black shoes, tan tights/stockings, black cape with red lining. You were not allowed to go home in uniform.

Our training involved working 12 months at the District Hospital in West Bromwich. Then you had a choice between Heath Lane hospital, which was an elderly care unit, and a chest outpatient department and a chest ward – Moxley hospital, which was an elderly care unit – or an elderly care unit, or Smethwick Neurological Hospital, which at the time was the Midland Centre for Neurology, covering Wales, some of the south and the north. I was at Smethwick for three months and enjoyed every minute of it. Patients were admitted with head injuries, tumours, and neurological disorders – for example multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease. The wards were lettered i.e. F Ward. A new block was built with 10 wards. While there I lived in the nursing home. My room overlooked the graveyard, as the hospital in the past had been an infection hospital (smallpox). There were trees in the graveyard, which in the winter months became very sinister, especially more so around Halloween. My bedroom windows definitely stayed shut. On or off duty days or on our late shifts we could have breakfast in bed delivered by the kitchen waitresses to our rooms. My friend, who was in the room next door had a restless night so came into my room. We spent most of the night talking and taking it in turns to remove our hair rollers that were sticking into our scalps. Next morning when we had our breakfast delivered the waitresses had a shock as we’re both sitting up in bed together giggling.While there, we still had to attend Hallam for lectures. That meant getting two buses from the Neuro. One day we came out of the grounds to find a bus on its way, so my friend and I began to run up the hill to the bus stop. By the time we got to the stop we both out of breath. The bus driver had been sounding his horn as we approached but we didn’t realise he was trying to tell us that he was taking the bus back to the garage. We told him we were nurses and that we would be late for our lecture, asking what time next bus was due. He told us to get on the bus he took us all the way to the Hallam, dropping us off outside the hospital grounds.

~

Some of my Hallam Hospital memories include:

Hot summer days spending off duty time around the swimming pool.

The restaurant being segregated by screens, for the consultants, sisters, staff nurses, domestics, junior nurses, porters and other ancillary staff.

The feeling of family amongst the staff, from doctors to domestics, porters, painters, electricians.

Lifelong friends.

First trip to the mortuary: the mortuary was down a steep slope, with a sharp corner at the bottom. One night, taking a body to the mortuary, a bird flew out from a tree, I screamed and let go of the trolley. The porter, who had the trolley at the front, lost control and the trolley careered down the slope and hit the wall at the bottom. No damage to the corpse and a few dents to the trolley!

Making apple pie beds for nice looking young males.

Playing tennis on the courts.

Duty time in the nurses sitting room with two chairs together huddled in your cape catching up on sleep (split shifts).

When you were a junior nurse on night duty, you were selected to go to the nurses’ home at 10 pm to lock-up; all nurses living in had to be into this time. The grounds were open and on a winter’s night, frosty, icy, snowy, you were wrapped up in your cape, knowing as soon as you left the nurse’s home someone would come down and unlock the door to let the latecomers in. Then at 6 am you went back there to call the early shift nurses up and open up the doors. The nurses who were off duty had signs on the doors – ‘Do not disturb’.

Sitting in the classroom at Hallam Hospital on study days, listening to a consultant’s lecture, a summer’s day, windows open, the smell of grass being mown and the eyelids drooping.

On night duty on the children’s ward, lights went out at 9 pm. The girls were asleep, the boys more difficult, at about 9.15 pm the night sister would begin her rounds. The boys would be under the bedclothes making very loud snoring noises, and the sister would stop at each bed and ask all about that child at the end of the round and she would say ‘Thank you, Nurse Hooper, you did well to get them all to sleep so quickly’ knowing full well that they would be all out of their beds as soon as she left the ward.

My first deceased patient. I went to tell the ward charge nurse that the patient didn’t look very well. When he came to visit the patient, he told me he had died I cried.

Being sent to Barnsley Hall mental institution with a patient from the medical ward in an ambulance. When we got to the hospital, I needed the toilet. I settled the patient, then asked the nurse for the toilet. She showed me the way. As I was on the toilet there was a tapping on the door. I timidly said ‘Yes?’ and the nurse said I should have taken the key in with me, but she would wait outside the door. Needless to say I wasn’t in there long.

Theatre sister ringing the surgical ward I was on, and asking for a Kirschner wire, but when I asked the ward sister I couldn’t remember the name. She made me go to the Theatre to ask the sister what she wanted, which she told me in no uncertain terms. Scary. (Kirschner wire is used in orthopedics and other types of medical and veterinary surgery. They come in different sizes and are used to hold bone fragments together.)

Working on female medical on night duty to the winter months. There had been numerous deaths on the ward for 2 to 3 weeks. I asked the sister if I could change wards for a break. She changed me to female surgical. I went on duty at 8 pm, opened the door into the long ward to say good evening and the patient in the first bed passed away. I thought I was jinxed, but I survived.

~

I couldn’t eat while on nights, as your meal was usually about 1 am. My duty began at 8 pm and ended at 8 am the following day. I took a pair of soft slippers which I would wear when I was going around the ward, making sure all the patients were asleep safely, not trying to get out of bed, climbing cot sides or – as one retired nurse did one night – walk around naked, throwing the bedside curtains open as a consultant on call was examining a patient who just been admitted to the ward as a medical emergency. It took some persuasion to get her back into bed.

When the night sister came to do her rounds, we were always pre-warned she was on her way by the staff on the ward she had just visited. This one night the telephone didn’t ring with a warning. When you were on nights you sat just inside the ward and the first I knew that the night sister had arrived was when she said, ‘Nurse!’ I jumped out of my chair, looking at her in amazement. She did her ward round, asking me questions about the patients, what they had been admitted for, what investigations they had, or what investigations they were due to have, which you had to know. We returned to the end of the ward and I was breathing a sigh of relief that I knew all my patients. Night sister looked down at my slippers and said ‘Nice slippers, nurse, but not actually uniform policy.’ I got the message.

Because Hallam and District hospitals were old establishments, the wards were the Nightingale style. There were two parts to each ward, the long ward’s and the short ward, the latter being the elderly care ward. You got used to seem very large cockroaches scurrying across the floor. After duty in the long winter nights, which were not very pleasant as you never saw much daylight (as you slept most of the day), I used to catch a bus to go home. On the bus were the young girls going to work, make-up and hair immaculate, chatting about what they had done and where they had been the night before. I sat on the bus having a job keeping my eyes open and on occasions falling asleep, missing my stop and having to walk home from the terminus, about 15 minutes walk. I used to see a lady on theus on her way to work at a factory and her stop was the one I got off at, so she would tap on the shoulder when the stop was reached if she didn’t sit by me. I lost weight whilst on the night duty, dropping to 7 ½ stone. I lost 13 lbs.

~

Here are some memories of the District Hospital.

I was at the District Hospital from 1968 to 1969, as part of my nurse training. I worked on Kendrick ward, which was male medical, Salter male orthopaedic, Farley female medical, Chance female orthopaedic. I did night on Salter ward, my theatre experience and worked on Accident and Emergency.

One of the consultants at the District was Mr Kirkham. He was also West Bromwich Albion’s football team doctor, which meant that we often had Albion players of the day on the orthopaedic ward, with fractured legs, ankles, and knee injuries. Hero worship.

At the time I was there, the changeover from metal bedpans to papier-mâché ones with plastic bases was being introduced, along with the introduction of the bedpan disposal units. These machines were frequently overloaded and it was amazing how far papier-mâché can travel across a sluice. A mop and bucket was always on standby in the early days of this ‘new’ disposable time. We used to forget to put the bedpan into the base, but we weren’t naive for very long.

I returned to the District Hospital 1975 to work on Bache ward, which was women’s surgical. The two side wards had children having correction squint surgery and there was a balcony that had eight beds for children. On the balcony leaked so every time it rained the beds were moved inside the general ward. The ward space was tight with chairs in the centre of the ward for patients to sit on, plus footstools so when the doctors came to do their ward rounds the note trolley was left at the ward table and the notes had to be carried in your arms. The beds were close together, so to carry out any procedure required a bedside locker being moved aside. At that time there were vases of flowers sitting on the lockers, so inevitably the vases would be knocked over with smelly water being spilt. There weren’t any bed screens curtains. The screens were on wheels. We had waterbeds in use, which were not ideal for patients requiring bed baths, or for any other procedure.

On Bache ward there wasn’t a lift. Bache was up two flights of stairs. Patients returning from theatre, usually semiconscious and still with an airway in their mouths, would be wheeled on a stretcher to the bottom of the stairs. Under the patient would be a stretcher cloth made of calico type material with a slot either side to insert two wooden poles. Two porters would then carry the patient on the stretcher to their bed. The nurse would be monitoring the patient on the way up the stairs in regards to the airway, any intravenous in fusion or blood transfusion and other tubes. Some of these patients could be rather heavy.

Each week, Hallam and District were on a rotational on-call. If Hallam or District hadn’t any empty beds there would be transferring the fit patients to the hospitals not on call, but there would always be extra beds on the ward.

Fracture and orthopaedic clinics were held in Outpatients Department, which was part of the Casualty Department. Other clinics were held every day, Monday to Friday. The clinics were manic. There would be booked appointments and additions. The clinics that started 2 pm but ran until 7 pm – 8 pm. Seating arrangements were minimal; in the fracture and orthopaedic clinic there would be patients standing up, leaning on their wooden under arm crutches for hours, probably just having had Plaster of Paris casts removed.

For a few weeks the orthopaedic consultant was away and a locum came to cover who was from London. First of all, he didn’t understand the Black Country accent and he decided that children all required adenoidectomy, so there was a great rise in children attending the ear, nose, throat clinics.

~

These are just some of my hospital memories – as they say ‘you could write a book.’ Nursing in the 1960s was long hours and hard work but it was a happy time. I’m glad I did my training when I did and where I did it.”