For the West Bromwich at War 1939-45 project many people contributed stories, research and original source material. Here is but one example, contributed by his nephew John Sedgley.

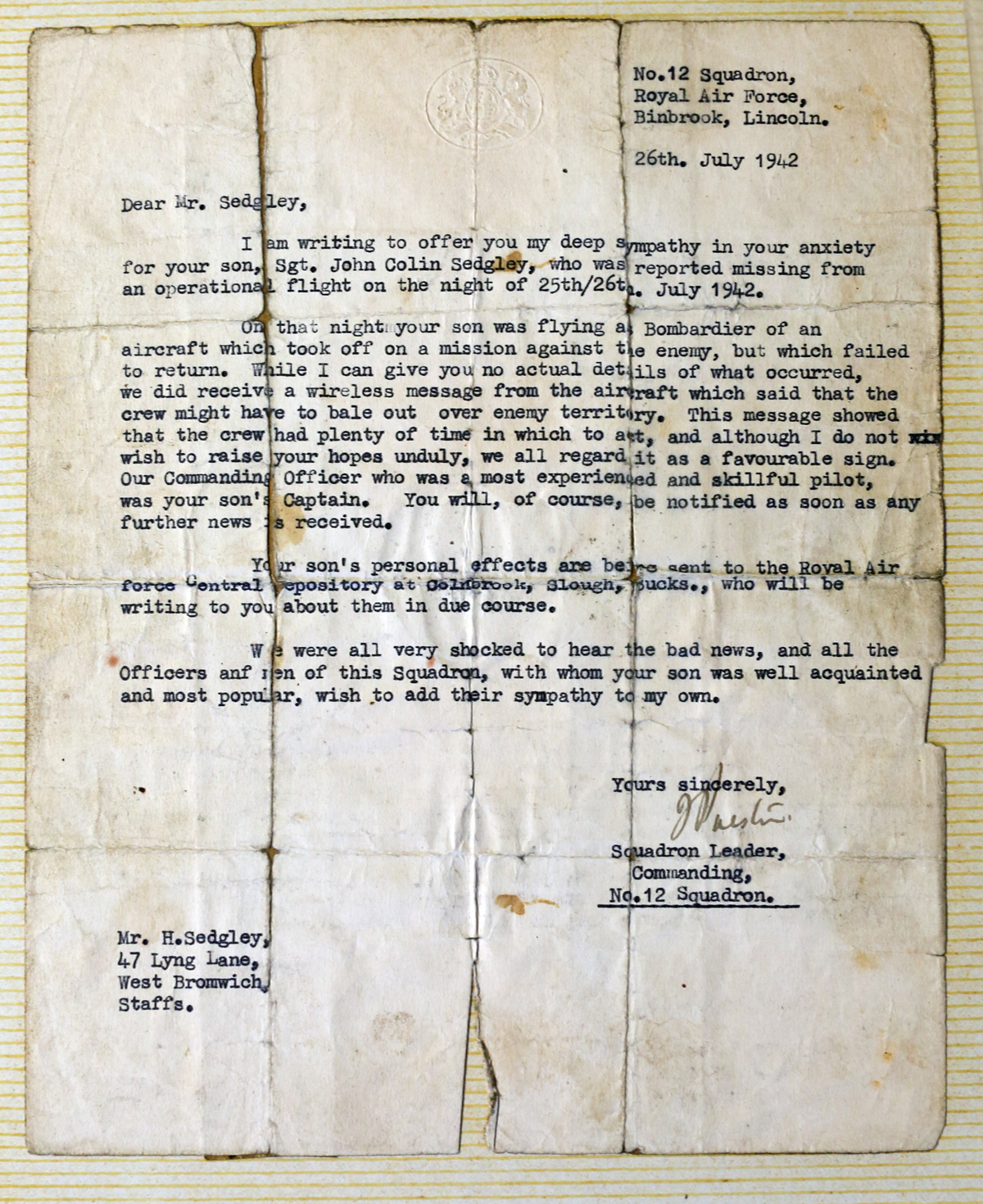

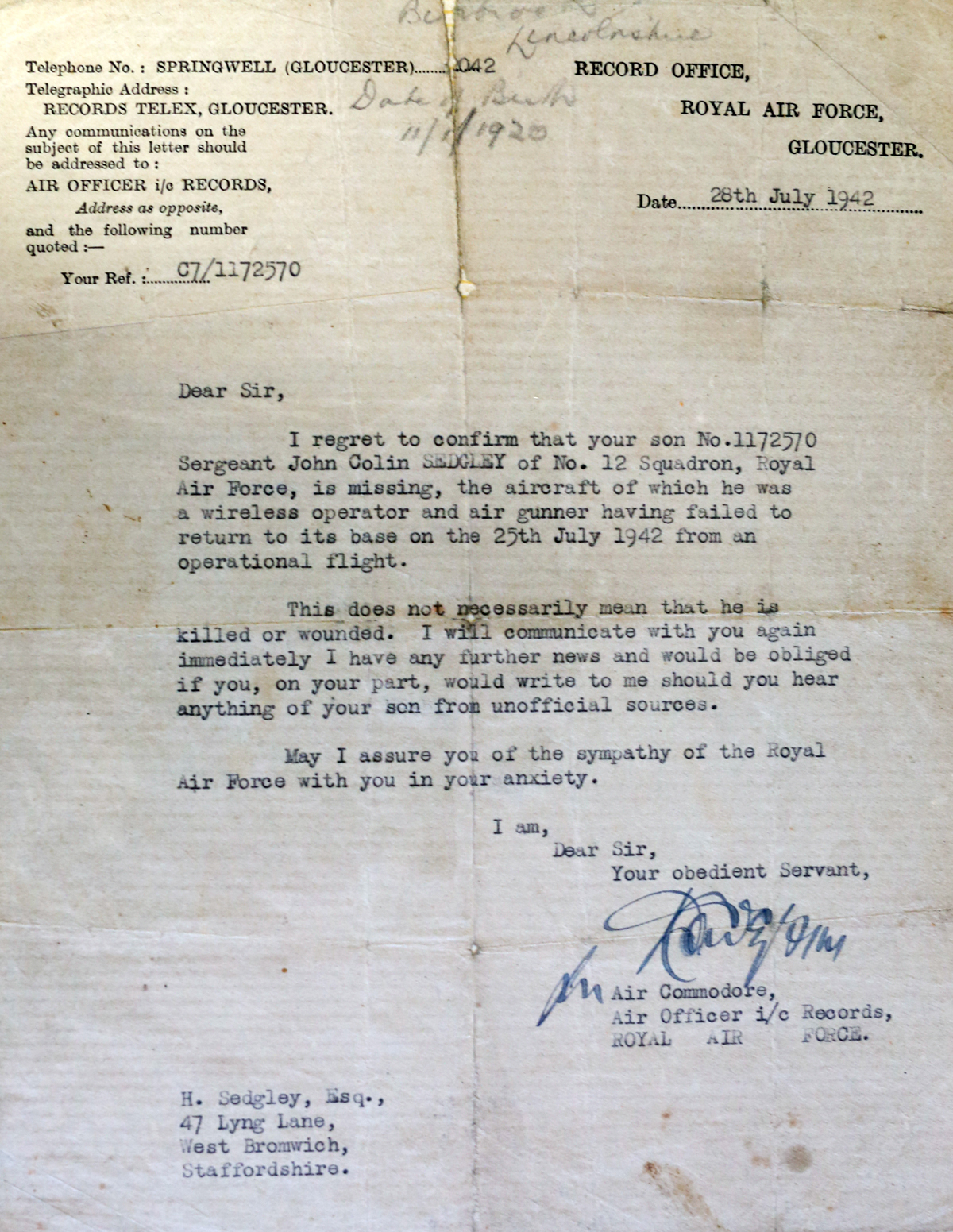

The father of 22-year-old Sergeant John Colin Sedgley, who lived in Lyng Lane, received a telegram informing him that his son was missing as a result of air operation. He soon received a letter from the Squadron Leader telling him that this occurred on the night of 25th – 26th July 1942. The letter stated: ‘While I can give you no actual details of what occurred, we did receive a wireless transmission from the aircraft which said the crew might have to bale out over enemy territory. This message showed that the crew had plenty of time to act, and although I do not wish to raise your hopes unduly, we all regard it as a favourable sign. Our Commanding Officer, who was a most experienced pilot was your son’s Captain.’

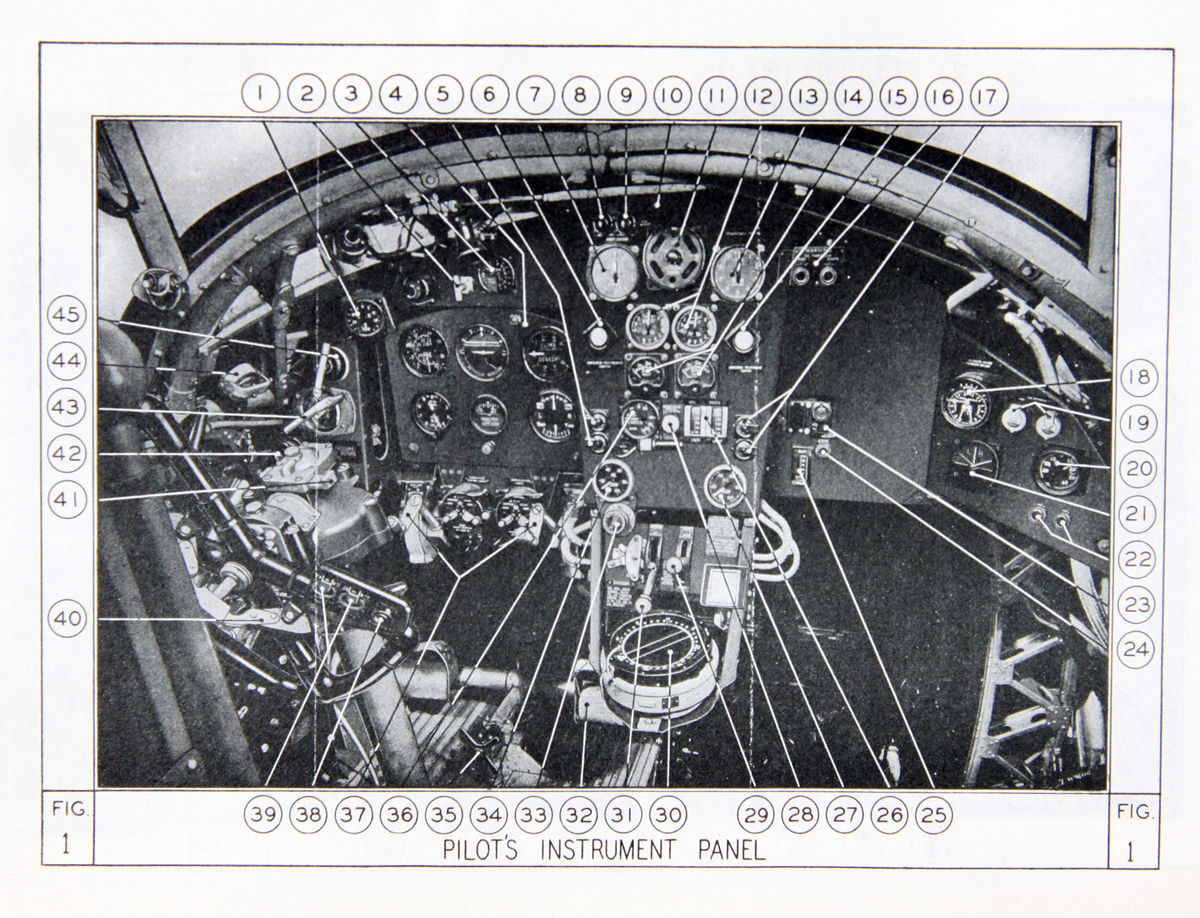

Wellingtons from No. 12 Squadron took off from Binbrook in Lincolnshire to take part in a ‘1000 Bomber Raid’ on Bremen. John was serving that night as a bombardier – atlhough he has also worked as both a radio operator and air gunner. He also has some flying experience and in a few weeks is due to be sent for Hurricane training. Fifty-five aircraft are lost this particular night. As John’s plane comes down over Holland, the crew bale out. One of the crew is killed. John finds himself in the middle of flat countryside, with a badly twisted leg. He comes across a farm and decides to knock on the door and ask for help. The farmer gives him civilian clothes and hides him in a nearby wood. Unfortunately, someone gives them away and later that day he is captured by the Germans. He is taken away and undergoes interrogation for two weeks, before being shipped to a Prisoner of War Camp in Poland.

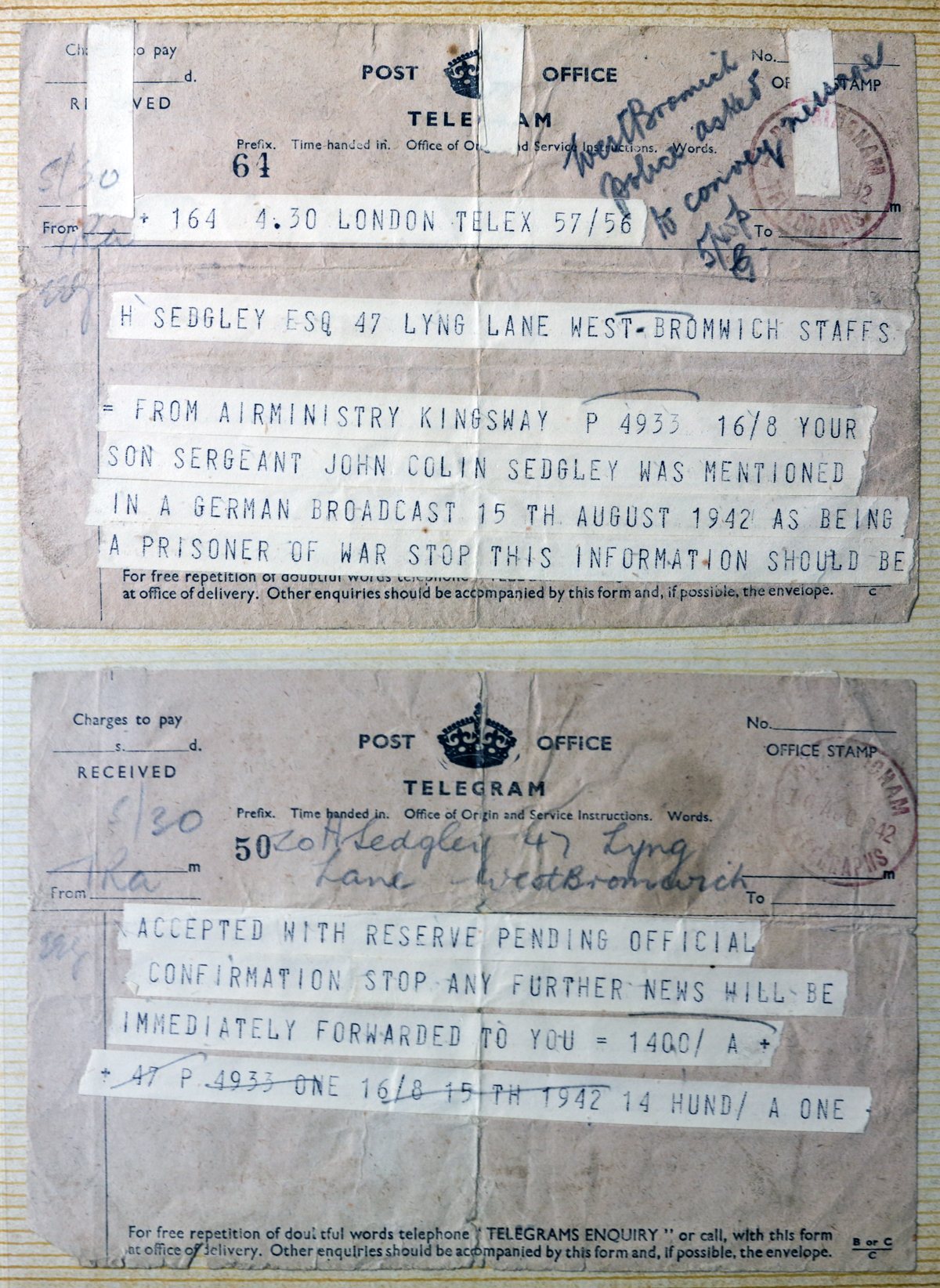

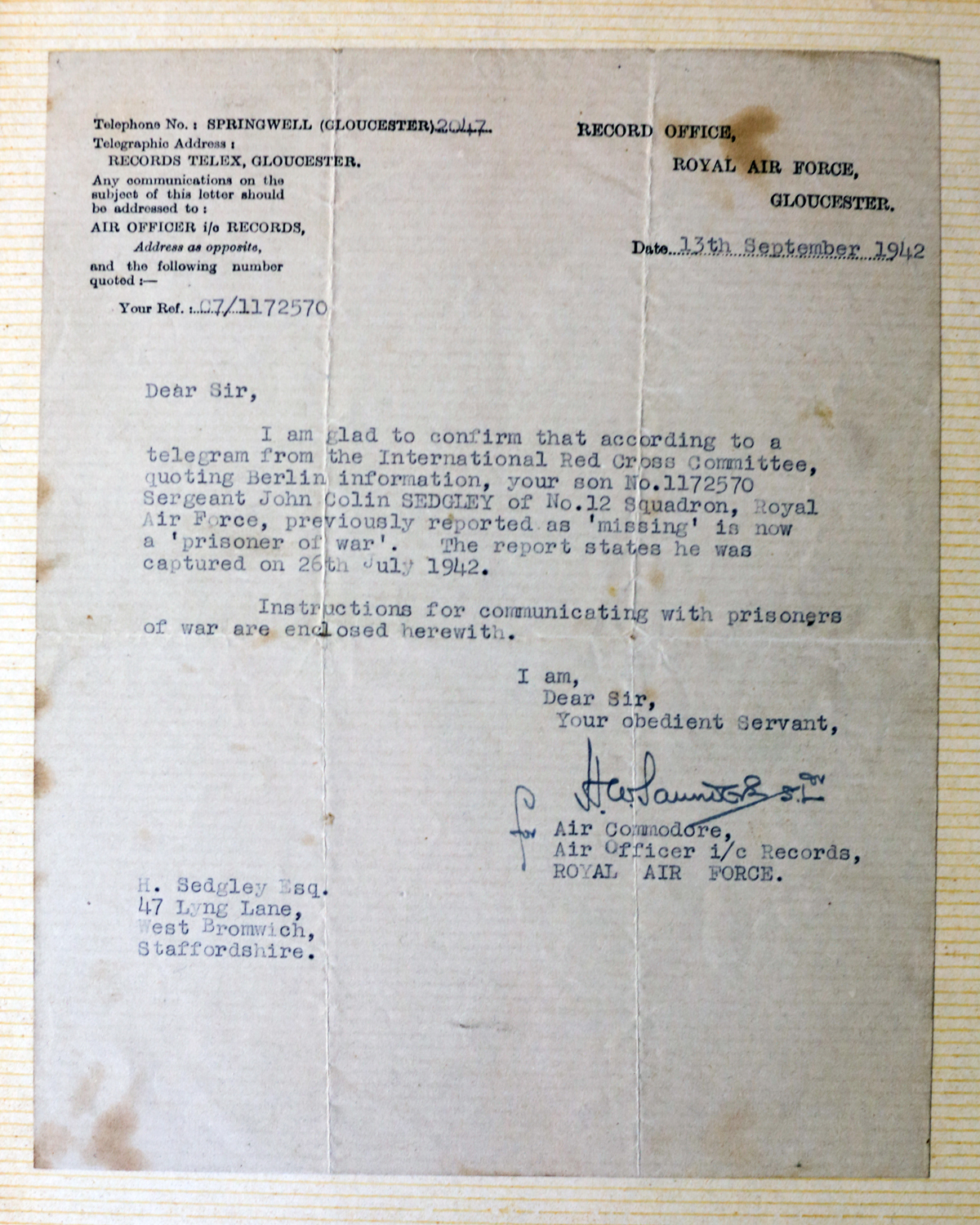

On 16th August, the Sedgley family received a telegram telling them that their son has been mentioned in a German broadcast as a POW, but that ‘this information news should be accepted with reserve pending official confirmation.’

The family were relieved to receive confirmation in September from the International Red Cross that John is indeed was alive and a POW. He spends the next two years in captivity, until in January 1945 the Russians finally launch a fresh offensive into western Poland. In the face of the rapid advance of the Red Army, the Germans decide to move their prisoners, including John. In bitter winter conditions, at bayonet point they are marched 15 to 25 miles a day to the west – resting in factories, churches, barns, even in the open. Weak and exhausted, he didn’t think he could walk even 10 miles, but he somehow he eventually makes it to a camp near Hanover. Here, one day, they awake to find the guards gone and a British Armoured Division coming down the road.

After his return to England, Sgt Sedgley spent a month or so recovering in hospital at Cosford. Soon after he met his wife to be Dorothy Lewis at a dance in Wolverhampton. They will have one daughter, Linda. John Colin goes to work at Accles and Pollock, then runs a pub for a few years, then he will work as a production manager for a company casting magnesium.

Decades later, he returned to Holland to again meet the Dutch family that tried to help him on that first night his Wellington crashed and he will visit the country often, even once meeting the King and Queen of the Netherlands.

-extracted from the book ‘West Bromwich at War 1939-45’