When Kenneth Savin left school he went to work with the Great Western Railway Company. An accomplished accordion player, he played in local pubs around West Bromwich. In October 1939, aged 20, he enlisted with the Suffolk Regiment. After several months training and various duties, which include the removal of bomb debris from the streets and docks of Liverpool and spells assisting farmers in Leicestershire and Hertfordshire with their harvests, his battalion was shipped overseas in November 1941. Leaving from Liverpool on the SS Andes, the soldiers assumed they were to be deployed in Egypt. Instead they crossed the Atlantic to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where they were put on another troopship, which carried 4600 men. The ship traveled to Trinidad, with no shore leave allowed, down the coast of South America and then across to South Africa. On 9th December, they arrived in Cape Town and heard the news that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbour. On 13th December they set sail for Bombay, disembarking on the 28th, then going to Ahmednagar in western India, to spend more weeks training and acclimatising to the intense heat.

On 19th January 1942, he left Bombay aboard USS Wakefield. Twenty days later, it was the first ship of their convoy to reach Singapore. Ships in the harbour were damaged and ablaze, under heavy air attack. As they docked they saw the RAF evacuating their personnel, not a welcome sign. Kenneth and his friends were not to know that at this point Japanese troops had captured most of the Malay Peninsula and were only 30 miles way. The island they are on, which now faced the full Japanese onslaught, only measured 13 miles north to south and 27 miles east to west.

They first took up positions around Fairy Point Hill on the north-eastern flank, overlooking the mile-wide Straits of Johore which divided Singapore from the south coast of Malaya. They could see enemy movements opposite. On 5th February, the Suffolks came under fire from Japanese mortars and took their first casualties. The only defences along the beachfront were bundles of empty tin cans strung along, suspended on wire just above the waterline. This was intended to act as an alarm in the event of a landing at night. The General Officer Commanding Malaya, Lieutenant General Arthur Ernest Percival, had dismissed repeated requests from his Chief Engineer to build fixed defences, saying ‘Defences are bad for morale – for both troops and civilians.’

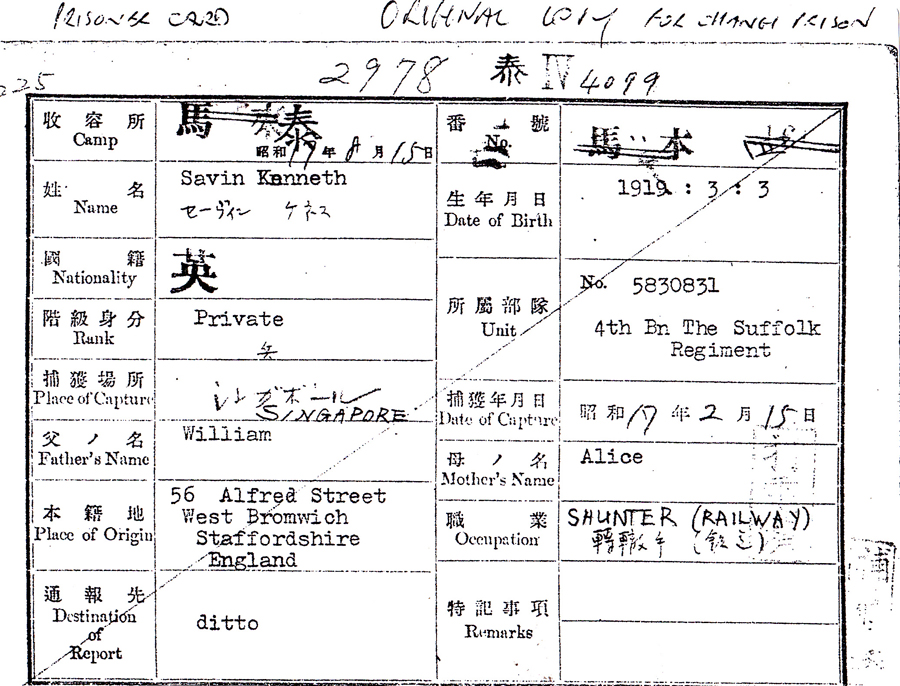

On the 11th, the Suffolks relocated from this beach to Bukit Timrah in the western area. The roads were congested, the troops had no adequate maps and became lost. After a 12-mile march they eventually reached their destination, the Swiss Rifle Club by Upper Pierce reservoir. Here they made immediate contact with the Japanese. On the 13th they suffered heavy casualties in hand to hand fighting on the Bukit Timrah golf course. They came under heavy fire from artillery and tanks and were forced to withdraw to Mount Pleasant Road, below MacRitchie Reservoir. On the morning of 15th February, with the Japanese breaking through the last lines of defence, with his troops running out of food and ammunition, General Percival surrendered. It is the largest capitulation of British-led forces in history, with over 100,000 troops going into captivity. Many thousands of Chinese residents were massacred by the occupying troops. Private Kenneth Savin was marched into captivity at Changi Prison, where he spent his 23rd birthday.

– extracted from the book ‘West Bromwich at War 1939-45’

Private Kenneth Savin travelled 20,000 miles, was in combat for seventeen days at Singapore, and then a prisoner of war. After Changi prison, he was then sent to work in various labour camps. One of their first tasks was to build a shrine at Bukit Timrah to commemorate the Japanese soldiers killed in battle. The conditions at the camps were poor and prisoners suffered from dysentery, malaria, beri beri as well as from tropical ulcers and ringworm, Though they were given inoculations against cholera. Their main diet was only rice. In October 1942, along with many other thousands he was transported to Thailand to work on construction of the Bangkok to Burma railway. On the 12th July 1943 he died at Tonchan camp, along the River Kwai. He is buried at Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, along with 6,981 of his comrades.

You can find more detail at this website, with information compiled by Mike Savin